단순히 관전만 해도 재미있지만, 규칙을 조금만 이해하게 되면 금세 F1은 감탄과 몰입의 대상이 되고, 다음 경기를 손꼽아 기다리게 될 것이다.

쉬운 것부터.. "그랑프리"란?

‘그랑프리(Grand Prix)’라는 용어는 프랑스어로 ‘위대한 상(great prize)’을 뜻하며, 이는 F1 경기가 다른 레이싱 시리즈보다 얼마나 중요한지를 상징한다.

모든 F1 경기는 그랑프리라고 부르지만, 모든 레이스가 그랑프리인 것은 아니다.

서킷(Circuits)

F1 시즌은 매년 다양한 수의 그랑프리가 국제 경기장에서 열리는 방식으로 구성된다. 시즌의 최소/최대 경주 수는 정해져 있지 않지만, 최근 몇 년간 경기 수는 꾸준히 증가하는 추세다.

모든 그랑프리 개최지는 FIA(Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile) - 월드컵축구에도 FIFA가 있듯이, F1자동차 경주를 주관하는 기관으로 FIA가 있다 - 가 정한 가장 엄격한 안전 기준을 충족해야 하며, 이는 드라이버와 관중 모두를 보호하기 위한 것이다.

축구에 익숙하다면, F1을 월드컵이라 생각하고 FIA를 FIFA로 생각하면 된다. 서킷은 폐쇄된 공공 도로나 전용 트랙 위에 조성되며, 출발점과 도착점이 같은 폐쇄 루트 형태다.

경기장(트랙)의 길이는 어떻게 되나?

1989년에 제정된 규칙에 따르면, 각 경주는 305km(190마일)를 주행하는 것으로 정해져 있다. 서킷마다 길이는 다르지만, 305km를 주행할 때까지 같은 트랙을 여러 바퀴 도는 방식으로 레이스가 진행된다. 드라이버가 305km를 채운 이후 결승선을 다음에 통과할 때 그 경주는 종료된다.

단 하나의 예외는 모나코로, 이곳의 좁고 복잡한 도심 서킷에서는 경주 거리가 260km로 짧다.

경주의 시작을 알리는 라이트 아웃(Lights Out)

그랑프리는 먼저 포메이션 랩(formation lap)으로 시작된다. 드라이버들이 트랙을 느린 속도로 한 바퀴 돌며차량을 점검하고, 각자의 스타팅 그리드(starting grid) 위치에 선다. 모든 차량이 제 위치에 정렬되면, 출발선 위에 있는 빨간 불 다섯 개가 차례로 켜진다. 다섯 개가 모두 켜진 뒤 예측할 수 없는 시점에 동시에 꺼지면 경기가 시작된다.

이 무작위 지연(random delay)은 반응 속도가 중요한 이유이며, 빠른 스타트를 위한 핵심 요소다.

F1 위크엔드의 구성(Weekend Format)

F1의 한 경주 주말은 보통 3일간 5개의 세션으로 구성된다.

금요일: 프리 프랙티스 1, 2 (연습 주행)

토요일: 프리 프랙티스 3, 예선(Qualifying)

일요일: 본경기인 그랑프리

예선 (Qualifying)

예선은 경쟁 세션의 시작이며, 그랑프리 출발 순서를 결정한다. 가장 빠른 랩타임을 기록한 드라이버는 폴 포지션(pole position)에서 출발하고, 가장 느린 드라이버는 뒤쪽에서 출발하게 된다.

예선은 총 3개 세션(Q1, Q2, Q3)으로 구성된다.

Q1: 18분 – 하위 5명 탈락 → 20~16위

Q2: 15분 – 하위 5명 탈락 → 15~11위

Q3: 12분 – 상위 10명이 최종 순위 경쟁 → 1~10위

각 세션 사이에는 짧은 휴식시간(7~8분)이 있다.

중국에서도 F1레이스가 펼쳐진다는 게 그건 무슨 경기인가요?

2021년 도입된 스프린트(sprint)는 일부 주말에만 진행되는 100km짜리 단거리 레이스다.

기존의 세 번째 프리 프랙티스를 대체하며, 별도의 예선과 함께 토요일에 치러진다.

2025년 기준 스프린트 개최지:

중국

마이애미

벨기에

미국(오스틴)

브라질

카타르

그랑프리 본경기

그랑프리 본경기는 모든 주말 세션의 결실로, 305km를 주행하며 가장 먼저 결승선을 통과한 드라이버가 우승한다. 이때 지켜야 할 규칙도 있다:

F1은 비접촉(non-contact) 스포츠이므로, 상대를 트랙 밖으로 밀어내면 안 된다.

최소한 바퀴 한 개 이상은 트랙 경계선 안에 있어야 하며, 무리한 트랙 이탈은 제재 대상이다.

경주 중 두 가지 종류의 타이어를 사용해야 하며,

경기 후 샘플 연료를 검사할 수 있을 만큼 충분한 연료를 남겨야 한다.

타이어(Tyres)

F1 머신의 네 타이어는 ‘컴파운드(compound)’라 불리는 다섯 가지 종류로 구분되며, 본질적으로는 모두 단순한 고무 디스크 형태다. 경기가 건조한 조건에서 열릴 경우 드라이버는 트레드(홈)가 없는 슬릭(slick) 타이어를 사용한다.

슬릭 타이어는 다시 소프트, 미디엄, 하드 세 가지로 나뉘며,

소프트 타이어는 접지력은 가장 좋지만 마모가 빠르며,

하드 타이어는 접지력은 낮지만 더 오래 지속된다.

인터미디엇(Intermediate) 및 웨트(Wet) 타이어는 빗길이나 젖은 트랙에서 사용하는 홈이 있는 타이어다.

건조한 레이스에서는 드라이버가 슬릭 타이어 중 최소 두 종류를 사용해야 하며, 그렇지 않을 경우 FIA로부터 실격 처분을 받게 된다.

피트 레인(Pit Lane)과 피트 스톱(Pit Stops)

피트 레인은 F1에 참가하는 10개 팀의 본부가 있는 곳으로, 레이스가 시작된 이후 차량에 사람이 접촉할 수 있는 유일한 장소다. 여기서 타이어 교체, 수리, 차량 셋업 조정 등 레이스 중 가능한 모든 작업이 이루어진다.

드라이버는 레이스 중 원하는 만큼 피트 스톱을 할 수 있지만, 시간이 많이 소요되기 때문에 최대한 피트인 횟수를 줄이는 전략이 중요하다. 피트 스톱에는 최대 시간 제한은 없지만,

안전상의 이유로 최소 시간 제한은 존재한다.

예를 들어:

휠을 장착하고 차량이 바닥에 내려가기까지 최소 0.15초,

차량이 출발하기 전까지 추가로 0.2초가 있어야 한다.

또한, 피트 레인에서 위험하게 복귀하거나 다른 차량을 방해하면 페널티를 받을 수 있다.

피트 레인 제한 속도(Pit Lane Speed Limit)

F1은 속도의 스포츠지만, 피트 레인에서는 속도 제한이 철저히 적용된다.

대부분의 서킷에서는 80km/h가 제한 속도이며,

일부 서킷은 이보다 더 낮을 수 있다.

속도 위반 시, 1km/h 초과할 때마다 100유로의 벌금이 부과되며, 최대 1,000유로까지 부과될 수 있다.

파르크 페르메(Parc Fermé)

이 구간에서는:

전면 윙 조정

연료 보충

액체 배출 및 보충만 허용된다.

모든 작업은 FIA 기술 위원이 입회한 상태에서만 가능하다.

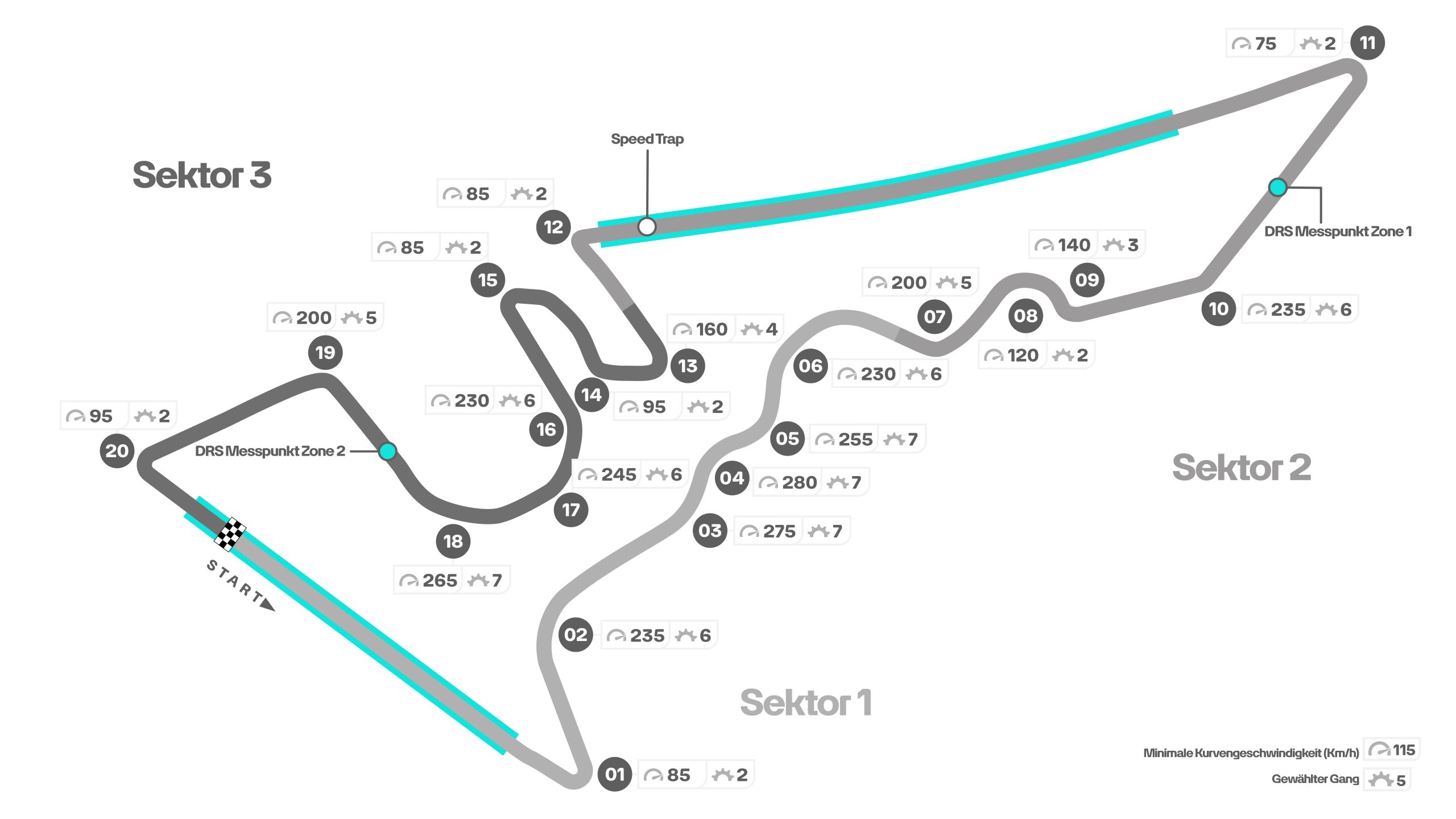

DRS(Drag Reduction System)

2011년에 도입된 DRS(공기 저항 감소 시스템)는 리어 윙의 일부분을 열어 공기 저항을 줄이는 기능으로, 직선 구간에서 추월을 쉽게 하고 레이스를 더욱 흥미롭게 만든다.

프리 프랙티스와 예선에서는 DRS 존에 진입하면 자유롭게 사용 가능하지만,

레이스 중에는 앞차와의 거리가 1초 이하일 때만 사용 가능하다.

이때 앞차는 추월 대상 경쟁자일 수도 있고, 랩다운(한 바퀴 차이) 차량일 수도 있다.

까다로운 차량 규정(Car Regulations)

F1 차량은 FIA가 사전에 설정한 정밀한 기술 규정에 따라 제작된다. 이 규정은 엔진 성능부터 타이어 압력, 차량 무게, 공기역학 디자인 범위까지 모든 것을 포함한다.

예를 들면:

차량의 최소 무게는 796kg,

백미러 크기는 150×50mm,

경기 후 연료 샘플용으로 1리터 이상 연료가 남아 있어야 하며,

공기역학적 디자인에서 허용된 영역과 제한된 영역이 구분되어 있다.

FIA는 이 모든 규정을 공식 홈페이지에 170페이지 이상 문서로 게시하고 있다.

포인트는 어떻게 획득하나요?

포인트는 상위 10위권 드라이버에게만 부여되며, 이 포인트를 기반으로 시즌 중 드라이버 챔피언십과 팀 순위가 결정된다.

1위: 25점

2위: 18점

3위: 15점

4위: 12점

5위: 10점

6위: 8점

7위: 6점

8위: 4점

9위: 2점

10위: 1점

추가로, 최고 랩타임을 기록한 드라이버는 1점을 더 받을 수 있지만, 10위 이내에 들어야 유효하다. 스프린트 레이스에서도 상위 8명에게 포인트가 주어진다. (1위: 8점, 8위: 1점)

한 팀의 두 드라이버가 얻은 포인트는 합산되어 팀 순위에 반영되며, 예를 들어 한 팀이 1-2위 + 패스티스트 랩을 하면 최대 44점을 얻을 수 있다.

F1 레이스에서 깃발을 흔드는 게 참 멋있어 보여요(Flag Rules)

F1 경주 중, 트랙 사이드의 마셜들이 흔드는 깃발은 드라이버에게 시각적으로 상황을 알리는 신호이며, 모든 모터스포츠에서 사용되는 국제 공통 신호 체계다. 현대 F1에서는 LED 보드와 함께 병행하여 사용된다.

노란 깃발 (Yellow Flag): 앞에 사고 또는 위험이 있으니 감속하고 추월 금지

한 개: 감속

두 개: 정지 준비

초록 깃발 (Green Flag): 위험 구간 통과 후 정상 주행 가능

빨간 깃발 (Red Flag): 사고, 기상 등으로 인해 경기 중단 → 피트로 복귀

파란 깃발 (Blue Flag): 뒤에서 빠른 차량이 접근 중이니 양보 필요

3회 이상 무시 시 페널티

흑백 깃발 (Black and White Flag): 비신사적 주행(코너 커트, 과도한 압박 등) → 최후 경고

검은 깃발 (Black Flag): 주행 기준 미달 → 실격, 피트로 복귀

검은 깃발 + 주황색 원 (Meatball Flag): 차량 기계 결함 → 즉시 피트로 들어가 수리

체커 깃발 (Chequered Flag): 세션 종료(연습, 예선, 본경기) 신호