The Age of Unprecedented Global Attention to Korean Culture

We are living in a time when global interest in Korean culture is higher than ever before. Yet, despite this surge in recognition, many foreigners—though familiar with the name “Korea”—still confuse South Korea with North Korea or are unaware that the Korean Peninsula is divided at all. Interestingly, major Korean corporations enjoy far greater international recognition than the country’s political circumstances.

In fact, in many cases, teenagers in Latin America can name more K-pop idols than many Koreans in their 40s and 50s. This shift has led professionals in Korea’s cultural sectors to put even more effort into sustaining and expanding the global phenomenon of Hallyu, or the Korean Wave.

|

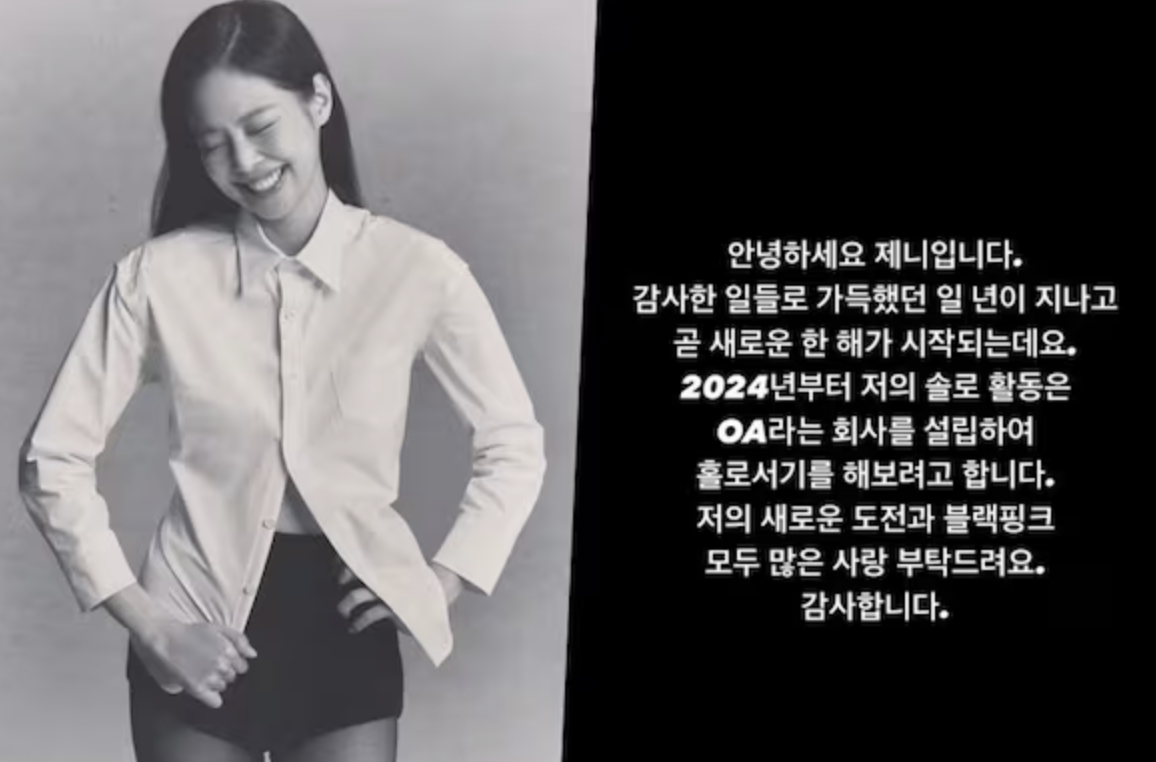

| Jenny's comment |

|

The Paradox: Rising Culture, Declining Literacy?

However, in contrast to Korea’s rising cultural influence, concerns have been voiced about a decline in national literacy. At one point, the media ridiculed Korean youth for being unable to read even basic Chinese characters, or for giving absurd answers in spelling or grammar tests. This sparked debates about a supposed “literacy crisis” among younger generations.

Some critics attributed this decline to a shift in media consumption—from text to video—and to students focusing more on rhythm than lyrics when listening to music, or spending more time studying English and other foreign languages at the expense of Korean reading comprehension.

|

| Literacy levels of Korean adults compared to the average literacy of adults in OECD member countries |

But the Data Says Otherwise

Recent studies, however, tell a different story. In the 2024 OECD literacy assessment, South Koreans aged 16 to 24 scored an average of "276" points in language proficiency. In contrast, those aged 35 to 44 scored "259", and the so-called "Chinese-character generation" aged 45 to 54 scored "244". This last figure is a full 29 points below the OECD average of 273.

This suggests that, contrary to popular belief, younger generations—those accustomed to digital media, global languages, and evolving forms of communication—are actually reading and interpreting modern texts more effectively than their elders.

Literacy Today: More Than Just Reading Words

As time passes, language evolves. The generation fluent in Chinese characters is being replaced by one fluent in digital and global expressions. In the past few years alone, the rise of the internet, AI, and social media has birthed entirely new forms of language and interaction.

In this context, literacy should not be defined solely as the ability to read printed words. Rather, it should include the ability to engage with and interpret a diverse range of texts—online posts, public documents, apps, and more—at a level sufficient for real-world communication.

|

| The issue lies not with the students, but with the adults. |

Literacy as Practical Skill: My Experience with the JLPT

Of all foreign language exams I’ve taken, the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) stood out to me. The reading comprehension section includes materials commonly encountered in daily life—announcements from public offices, course guides, train ticketing instructions, and so on.

Many questions required choosing the most appropriate response based on a realistic scenario, like selecting a train pass that best fits one’s travel schedule. Interestingly, many of these scenarios assume the information is accessed online.

Exposure Matters More Than Technology

It’s not just about whether you can use digital tools, or how often you use them. Students are immersed in reading environments through textbooks, required readings, and study materials. According to a 2024 survey by Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, 95.8% of primary and secondary students read at least one book per year, and the average annual number of books read per student was 36.

That’s roughly three books per month—a figure that implies high exposure, even if depth of reading may vary.

The Adult Gap: Who’s Really Reading?

What about adults? The situation is starkly different. The adult reading rate stood at only 43.0%, less than half that of students. The average number of books read by adults was just 3.9 per year—roughly what students read in a single month.

Ironically, 2024 was also the year when Korea saw its first-ever Nobel Prize in Literature awarded. Sales of Han Kang’s books soared, with some editions going into multiple printings overnight. For students, her work became essential reading—perhaps even exam material. Even if they read it because they had to, they still read it.

Meanwhile, adults—though they may buy such books—are far less likely to read them themselves.

A Nation Obsessed with Foreign Languages… but Falling Behind?

Korea has invested an enormous amount of time and money into English and foreign language education. The 40s and 50s age group studied English just as intensely as today’s youth—perhaps even more so.

Many 50-somethings attended English academies from elementary school, chased TOEIC scores above 900 to secure jobs, and poured years into language learning. Yet, ironically, this generation scores lower in actual literacy assessments.

|

| Following author Han Kang's Nobel Prize in Literature, a prolonged shortage of her works led Kyobo Bookstore to temporarily suspend sales of her books in an effort to support local bookstores. |

A Global Context: Should We Be Worried?

One might find some comfort in the fact that countries like France and Italy also score below the OECD average in literacy. Italy, in fact, ranks even lower than Korea.

However, this doesn’t mean we can afford to be complacent. Those countries face far less pressure to learn English, and their population structures and linguistic environments are more complex than Korea’s.

In other words, we can’t use their scores as an excuse. Korea’s unique cultural and educational intensity calls for a deeper reflection on what literacy truly means today.

No comments:

Post a Comment